Fresh off his Tour win, Sahith Theegala is embracing the first off-season of his career

Fresh off his Tour win, Sahith Theegala is embracing the first off-season of his career

Into the mystic: Golf in the Kingdom’s magical power still inspires, as does its visionary author

Almost 50 years ago, Michael Murphy penned what many consider to be the definitive book on golf — not that he knew it at the time. But to this day, the magical power and mystical musings of golf in the kingdom inspire, as does the unlikely story of its visionary author.

“Norman Mailer said every writer gets one book that is a gift from God,” says Michael Murphy with a twinkle, “and Golf in the Kingdom was mine.”

But which deity bestowed the gift? Was it Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and redemption, whose name is evoked by Shivas Irons, the mysterious Scottish teaching pro at the core of the novel? Is it the Episcopalian god the young Murphy served in the 1940s as an altar boy in his hometown of Salinas, Calif.? Perhaps it is Buddha, whose teachings first entranced Murphy in the comparative religion class he took at Stanford, the seminal experience of his life, which set him off on a quest to become, in his felicitous phrasings, “an astronaut of inner space” and “lead a Manhattan Project of the psyche.” Maybe the book was a present from the very golf gods that beguile and bewitch us all, given to Murphy so he could help us make sense of an inexplicable game of which he writes, “How often have we seen a round go from an episode out of The Three Stooges to the agonies of King Lear — perhaps in the space of one hole?” When Murphy talks of the writing of GITK, his first book and, indeed, his first attempt to write one, he speaks in biblical terms, saying, “It came like a flood.”

That the very spark of GITK remains a mystery to its author should come as no surprise considering the book has been disorientating readers ever since its publication in 1972. The first half of it is a tale in three acts: a young Californian named Michael Murphy is on his way to India to study the teachings of the guru Aurobindo but first stops in Scotland, where he plays a round of golf in which, under Shivas Irons’ tutelage, his consciousness is altered and game unlocked. This is followed by a convivial dinner party where the meaning and mysteries of the game are discussed and debated. Finally, at midnight, Michael and Shivas return to the course (the fictitious Links of Burningbush, which shares much in common with the Old Course) in search of Seamus MacDuff, a sage and a seer who is Irons’ mentor. They never find this specter-like creature, but Shivas makes an ace in the moonlight using an old feathery and MacDuff’s only club, a crude Irish shillelagh. The second half of the book is a series of musings on the game, purportedly copied from Shivas’ journals.

Murphy wrote the book when he was 40. As a young man, in 1956, he had indeed stopped in St. Andrews on the way to study in India. In the years afterward, he cofounded the Esalen Institute, a retreat and research center on the cliffs of Big Sur dedicated to exploring and realizing human potential. It would become one of the epicenters of the counterculture (and is still thriving today). Murphy spent the 1960s expanding his mind — through meditation, hallucinogens, the study of ancient texts, and commingling with mystics and shamans. When he came out the other side, the story of GITK emerged from deep within his learned and agile mind. The slender volume — just over 200 pages — includes cameos from Saint John of the Cross, Plotinus, Pythagoras, Parmenides, Plato, the Koran, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the Bhagavad Gita, Pharaoh Ikhnaton, Pablo Picasso, Matthias Grünewald, Joan of Arc, Jean-Paul Sartre, Goethe, Meister Eckhart, Alan Shepherd and Sandy Koufax, to say nothing of Ben Hogan, Bobby Jones and Sam Snead. For some readers it is simply too much philosophical woo-woo. But for golf’s soul surfers, GITK is holy scripture.

“It gave us the language to talk about the spiritual side of the game,” says Brad Faxon, “which I had always believed in.”

Adds Peter Jacobsen, “In the late ’70s, I discovered my caddie Mike [Fluff] Cowan had one book in his possession — a copy of Golf in the Kingdom, which was all torn apart and held together by tape and rubber bands. I said, ‘What is this?’ He growled, ‘Only the best golf book ever written.’ And he was right.” Jacobsen estimates he has read GITK a dozen times.

“It’s so rich,” he says, “that every time I read it, I take away something new. It’s been very impactful on me in how I view the game. I love that line from Shivas, when he says golf is all about what happens in between the shots. [“If ye can enjoy the walkin’ ye can probably enjoy the other times in yer life when ye’re in between. And that’s most o’ the time; wouldn’t ye say?”] Reading that allowed me to understand that, while I had to concentrate over the ball, the rest of the time I could just be myself. I could interact with the gallery, I could laugh with my playing partners. Shivas taught me that.”

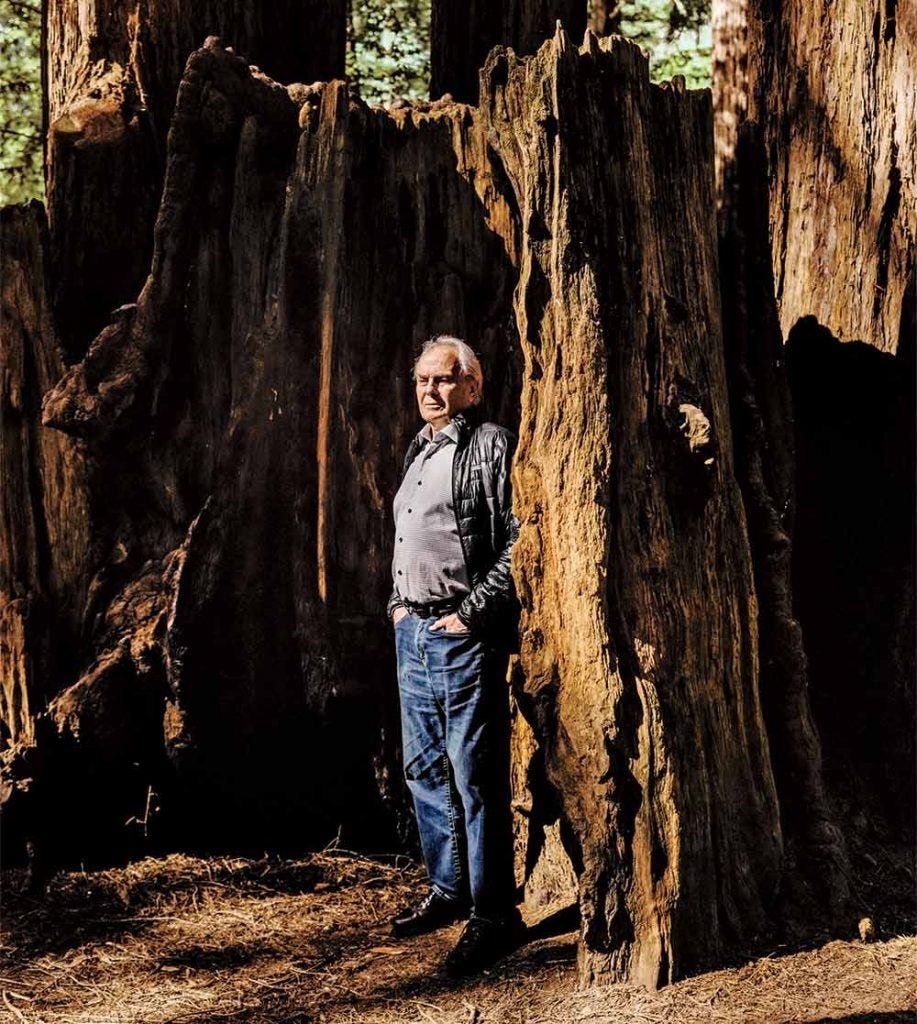

Murphy is now 89, his eyes as blue and alive as the ocean. He never tires of hearing these testimonials because all these years later he remains amused by his unlikely anointment as one of the game’s high priests. “When I wrote this book,” he says, “I never could have dreamed it would turn into something so much larger. What an unexpected adventure it’s been.”

* * * * *

Growing up in the 1930s and ’40s, Murphy was a baseball player who discovered golf in his teens. He quickly became good enough to challenge Ken Venturi in a couple of Northern California Golf Association events. Along with his brother Dennis, Murphy often made the 23-mile drive from Salinas to Pebble Beach to play the grand links, which back then carried a green fee of $5. The Murphy boys were also regulars in the gallery at the Crosby Clambake, back when it was the most glamorous event in golf. Michael was drawn particularly to Hogan and would often watch his practice sessions on what used to be an open expanse of land adjacent to the 2nd fairway. “There was a Zen aspect to it,” he says. “There was a great stillness all around him. Nobody spoke. Nobody moved. We just watched him. He was so focused it was like he was in a meditative state. There was such economy of motion in his swing, and in everything he did, really. It was beautiful to watch.”

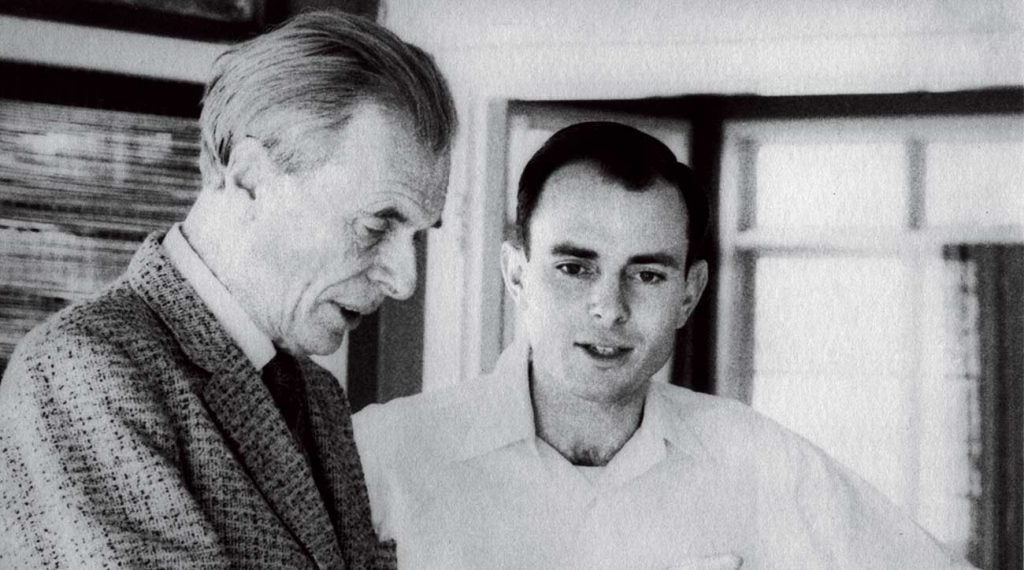

Murphy was born into a family of doctors — his grandfather Henry delivered John Steinbeck into the world (and, much later, a Dr. Murphy would appear in the pages of East of Eden). It was expected that Michael would uphold the family tradition, and it didn’t occur to the young altar boy to disobey; when he matriculated to Stanford he dutifully began a premed track. But during his sophomore year he took that comparative religion course and, as he would write in a slightly different context in GITK, “Something had broken loose inside me, something large and free.” He began meditating up to six hours a day, seeking to transcend the small-mindedness of the dusty farming town that had birthed him. Murphy finished his psychology degree in 1952 and then did a two-year stint in the Army. Having saved his paychecks from Uncle Sam, he set out to see the world. By the time he returned from Aurobindo’s ashram, he had a radical vision for the fallow piece of land his family owned in Big Sur.

His grandfather had purchased 375 acres along the coast in 1910, drawn by the natural hot springs that the Esalen Indians had used for thousands of years. He hoped to build a European-style recuperative hospital. Two World Wars and the Great Depression put those plans on hold indefinitely. Murphy tried to pitch his family on his vision of a retreat center, but they didn’t get it. “I mean, this was the 1950s,” he says. “Yoga, meditation, group therapy? They didn’t have any frame of reference for what I was talking about.”

But the hot springs were an open secret, attracting beatniks, bohemians, bikers, even a religious cult. On the weekends, an underground gay scene thrived. To watch over the property, the family hired a brawny young caretaker with a mean streak and dreams of being a writer: Hunter S. Thompson. As the legend goes, Thompson got into a beef with what Murphy calls “some muscle guys” and they threatened to throw Thompson off the cliff. He extricated himself and returned moments later, bloodied and packing an arsenal of firearms. The bullets had barely stopped whizzing when Murphy made another pitch to his family. They acquiesced, out of sheer desperation to put the land to use, and Esalen was born in 1962. (Murphy’s college classmate Richard Price is credited as cofounder.)

Eventually the larger world would discover the Eden they had created. As Murphy writes in GITK: “Psychiatrists, hippies, and swingers, learned men from universities and research centers, wounded devoted couples and gurus from the end of the world were descending upon us in answer to our letters and brochures. We were caught in a social movement we hardly knew existed. New adventures of the spirit were beginning, of the spirit and the body, of the spirit and the bedroom, of encounter groups and endless therapies — a vast exploration of what my teacher Aurobindo had called ‘the vital nature.’ ” It was in this milieu that, one night, Murphy happened upon his journals from his trip to St. Andrews nearly 15 years earlier. He sat down and started typing: “Suddenly, the feeling of it all, the smell of heather and those evanescent vistas of purple and green were there again in all of their original intensity….”

* * * * *

Murphy knows that some readers are baffled by GITK but he is unbothered. He cites one of the central metaphors of this century, by way of Harry Potter: “There are two kinds of people in this world: muggles and wizards. The wizards are a small minority, but that’s okay — they get to glimpse all the magic.”

GITK has been translated into more than two dozen languages and sold well over a million copies. (Seduced by a seven-figure advance, Murphy published a lively sequel in 1997, The Kingdom of Shivas Irons.) The book is so fundamental to how some golfers feel about the game that it has spawned the Shivas Irons Society, a nonprofit that brings together fellow travelers for golf trips and deep discussions about the book. “It gives voice to things that most of us are afraid to say,” says Society member Todd Rohrer, the founder of the gloriously old-fashioned, single-strap golf bag company Macdonald Leathergoods. “It’s a vehicle that allows me to explain why I play this silly game.”

Rohrer cites a few passages in the book in which Murphy has put into words the physical sensations that are often conjured during a round of golf: Shivas’ advice to banish swing thoughts by “letting the nothingness into yer shots”; his contention that the ball and sweet spot are already joined “afore ye started playin’ ” and all the golfer needs to do is return the club to this natural state; the bright turquoise line that appears in the mind’s eye tracing a shot in the sky before it has even been struck. “Golf is one of few pursuits when you can feel more than human,” Rohrer says. “Can you think of anything outside the bedroom that involves all fives senses? Or six? Michael tapped into all of that in a profound way.” Indeed, the olfactory imbues GITK; Shivas has “the smell of eucalyptus and baking bread, a powerful and distinctive odor.”

The book also captures the warm camaraderie that is at the heart of the golf experience. At the dinner party that Shivas and Michael attend after their round together, the hostess Agatha McNaughton gives an oft-quoted speech: “It’s the only reason ye play at all. Just look — ye winna’ come home on time if yer with the boys, I’ve learned that o’er the years. The love ye feel for your friends is too strong for that. All the waitin’ and oohin’ and ahin’ o’er yer shots, all the talk o’ this one’s drive and that one’s putt and the other one’s gorgeous swing — what is it all but love? Men lovin’ men, that’s what golf is.”

“Once you read the book, it makes you look for others who feel the same way about it,” says Society member Fred Shoemaker, a teaching pro based in Carmel Valley, Calif., and the author of Extraordinary Golf, a humanist instructional book. GITK would probably be even more popular if it consisted of only the first half, the more accessible tale of the protagonist’s 24 hours in an auld gray toon, but Shoemaker feels strongly that the esoteric and sometimes discursive treatises in the second half make the book. “We love something with a little mystery, something we don’t quite get at first,” he says. “The book, and especially the second half, is a Rorschach test. The words never change, but as the reader grows we see more and different things.”

Consider the golf ball. For many, it is just a thing to be whacked. In GITK, Murphy muses about its circular nature, just as a round of golf brings you back to where you began, a kind of endless journey that is “one of the central myths and signs of Western Man. It is built into his thoughts and dreams, into his genetic code.” The ball is “a reflection of projectiles past and future, a reminder of our hunting history and our future powers of astral flight.” At rest, it is “like an egg, laid by man.” The ball is “a satellite revolving around our higher self, thus forming a tiny universe to govern…. For a while on the links we can lord over our tiny solar system and pretend we are God; no wonder then that we suffer so deeply when our planet goes astray.”

Says Shoemaker, laughing, “Sometimes a ball is more than a ball.”

* * * * *

Murphy lives just north of San Francisco, in a lovely house amongst the redwoods, hard by a rushing river. He tries to walk at least three miles a day, often with his wife of 48 years, Dulce, who is just as vibrant as her hubby. He stopped playing golf years ago but the game still lives within him. He watches a lot of golf on TV, and cruising around this year’s U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, his old stomping grounds, Murphy couldn’t hide his delight. After glimpsing his favorite player, Tiger Woods, smash a drive, he said, “Watching the ball fly like that, I’m feeling something close to lust.”

It’s less than an hour’s drive from Pebble Beach to Esalen. The other day Murphy sat on the back lawn, enjoying a quintessential view: the roiling Pacific and two lovely young women sunbathing naked by the pool. Murphy stays at Esalen a dozen or so times a year, presiding over the Center for Theory & Research. It is devoted to social activism and citizen-to-citizen diplomacy, seeking to foster better relations between America and Russia (Boris Yeltsin visited the U.S. for the first time at Murphy’s invitation) and Israel and Palestine. In his fleece vest and hiking shoes, Murphy blended in well with all the other blissed-out visitors who were immersed in workshops and personal retreats. If any of them were golf fans they didn’t let on to recognizing the deity in their midst. But in the dining hall (where the organic, sustainable, locally grown vegetarian fare is delicious), one of the workers stopped Murphy.

“Hey, you’re that guy!” he said, pantomiming a golf swing with a spatula. Murphy loosed one of his boyish giggles, and a brief conversation about the game ensued. Sitting down to lunch, Murphy said something that sounded like one of Shivas Irons’ aphorisms: “You never know where or when you’re going to encounter a fellow golfer. It’s one of our most universal languages.”

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.