What made the Ryder Cup the Ryder Cup? You could argue 1983

Captains Jack Nicklaus and Tony Jacklin at the 1983 Ryder Cup.

Popperfoto via Getty Images

Barring pandemics, geopolitical unrest and other epic disruptions, the Ryder Cup will be played in Ireland in 2027 — and celebrate its 100th anniversary. You could argue it really started in 1921, when the editors of Golf Illustrated suggested to the PGA of America that the best U.S. pros play in the Open Championship at St. Andrews. The trip, per the proposal, would be paid for by public subscription. At a time when no U.S. player had ever won the Open, the idea resonated. Eleven American players (one opted out at the last minute) arrived a few weeks early and headed to Gleneagles, where, on the Monday before a proper tournament, a team of 10 British professionals took down Uncle Sam’s best. Turned out the bigger idea of improving the field at the Open worked. Jock Hutchison, born in Scotland but a newly minted naturalized U.S. citizen, became the first American winner. Such were the seeds of the Ryder Cup sown — or so you could argue.

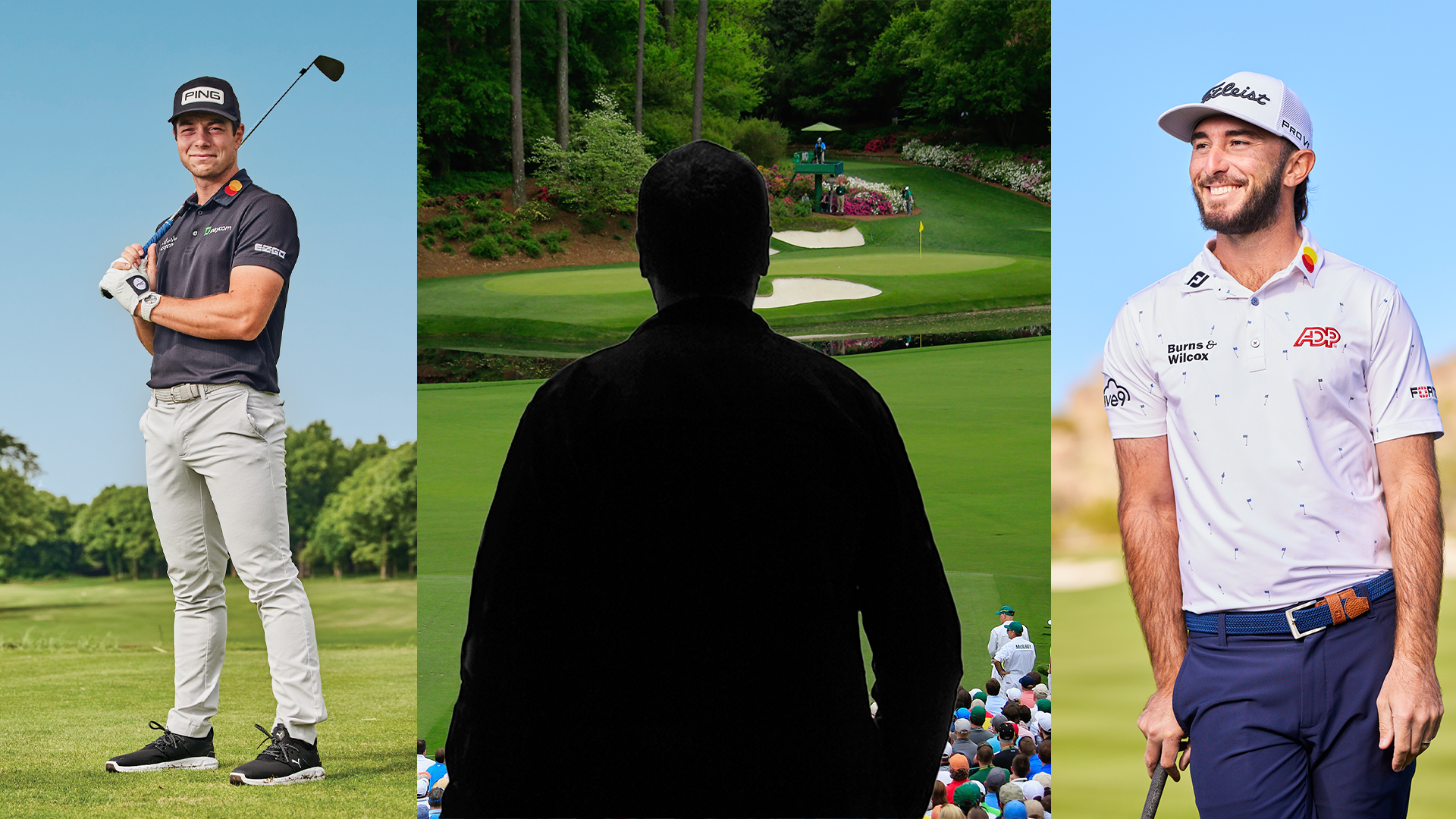

Over a pint with your mates, you could make an equally compelling argument that the Ryder Cup as we love it today was truly born 40 years ago, in 1983, at PGA National in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. Change had been brewing since 1979, when Seve Ballesteros and Antonio Garrido played on the first Team Europe. It was the first Team Europe because all prior teams included players from only Great Britain and Ireland (GB&I). Had that change never occurred, the game’s finest moments of dramatic theater and its ultimate crucible of guts, glory and nerve would today be undreamed.

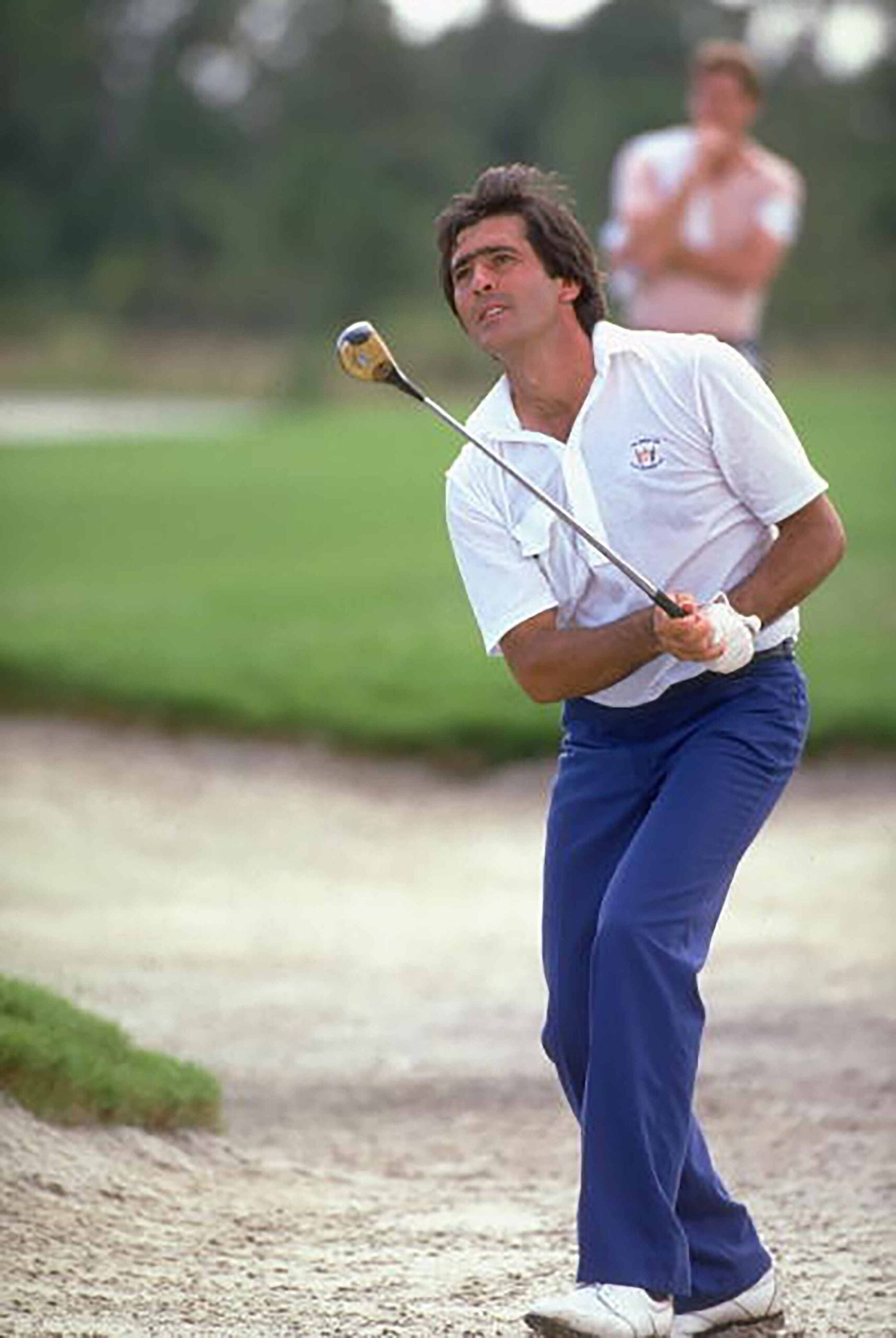

That change did happen, however, driven significantly by a desire on the part of Jack Nicklaus and Edward Stanley, Earl of Derby, then president of the Professional Golfers’ Association, to see a more competitive Ryder Cup. In the three decades after World War II, the U.S. had nearly swept the series, losing just once and playing to a draw on another occasion. For the most part, American teams had steamrolled GB&I — and did so again against Team Europe in 1979, when tickets at West Virginia’s Greenbrier were easily purchased at the gate for $15 on Friday and Saturday and $10 for Sunday singles play. Only 3,000 spectators turned out on Friday. Ballesteros and Garrido lost three times to one of the strongest U.S. duos ever, Lanny Wadkins and Larry Nelson. Nelson also took out Seve head- to-head in singles play on Sunday. Defeat didn’t sit well with Ballesteros, or with Nick Faldo, who, while not yet a major champion in ’79, showed signs (3-1-0) of the Ryder Cup beast he would become. “They knocked us over like tin soldiers,” said Faldo after the singles matches.

Still, hopes ran high so that in 1981, Team Europe, encouraged by particularly good four-ball and foursomes play in ’79, could swing the pendulum. Instead, they suffered the worst defeat they’d ever been dealt on British soil (18 1/2 to 9 1/2). To make matters worse, Ballesteros watched from the sidelines, left off the team due to an ongoing dispute over his acceptance of appearance money. “MASSACRED!” read the headline in London’s Daily Mirror.

In your closing argument with your mates, here’s why 1983 was the year the Ryder Cup became the Ryder Cup. After spirited play the first two days, both teams had eight points heading into Sunday singles. In the past, the script would have read: Cue Euro collapse.

But Tony Jacklin, the European captain, decided to send his top assassins out first, whereas U.S. skipper Nicklaus did the opposite. Ballesteros led the charge versus Fuzzy Zoeller and was 3 up after seven holes, thanks to four successive birdies. In a wild match, Zoeller then won four holes in a row starting at the 12th. Ballesteros birdied 16 to pull even and then played one of the most ridiculously amazing shots in Ryder Cup history to halve the match at 18. With his drive in the bermuda rough on the par-5 closer, he gouged his second into a bunker 240 yards from the green. He then lashed a 3-wood from the sand that barely cleared a greenside bunker. He got up and down to tie Zoeller, and the Ryder Cup legend of Seve was born. Nicklaus called the Ballesteros 3-wood “one of the most incredible shots I’ve ever seen.”

In the second and third matches, Faldo dusted Jay Haas and Bernhard Langer tipped over Gil Morgan. The U.S. won the next three matches; then Paul Way rolled Curtis Strange and Sam Torrance halved Tom Kite. With 10 matches done, the score was 13–13. Two matches were still in play on course. Tom Watson was fading in his match with future Euro captain Bernard Gallacher, and U.S. stalwart Wadkins had trailed José María Cañizares most of the day. Wadkins, however, had come back from three down and headed into 18 with a chance for a tie.

The mounting pressure — now a staple of the Ryder Cup, but then a novelty — got to Cañizares, and he left his simple approach of 90 yards short of the green in the deep bermuda grass. Wadkins, the era’s version of Captain America, stiffed a sand wedge and knocked in the birdie for a halved match.

Out at the par-3 17th, Watson, 1 up, and Gallacher had the Ryder Cup in their hands. Both had missed the green and joined a group of PGA officials with walkie-talkies to listen to the conclusion of the Wadkins-Cañizares match. In the end, Gallacher had a four-footer to push the match to the 18th. He did not make it.

“We just missed this time,” said Jacklin. “But, I promise you, when the Americans come to England in two years, it will be a different story.”

“The Europeans are going to win these matches,” said Nicklaus. “And they’re going to win them in this country.”

In 1985, Team Europe walloped the U.S. at The Belfry, in England, 16 1⁄2 to 11 1⁄2. In 1987, at Muirfield Village, with Jacklin at the helm for a third time and Nicklaus once again captain (Lee Trevino was the ’85 U.S. captain), Team Europe won 15–13, for its first ever win in the States.

You could argue that both Jacklin and Nicklaus were right about the future of the Ryder Cup in the immediate aftermath of Wadkins’ heroics in 1983 — and you’d be right.