Jon Rahm’s fury is here: Green jacket tears, Ryder Cup fears, gunning for history

From green jacket tears to Ryder Cup fears, Jon Rahm is fresh off the best season of his life.

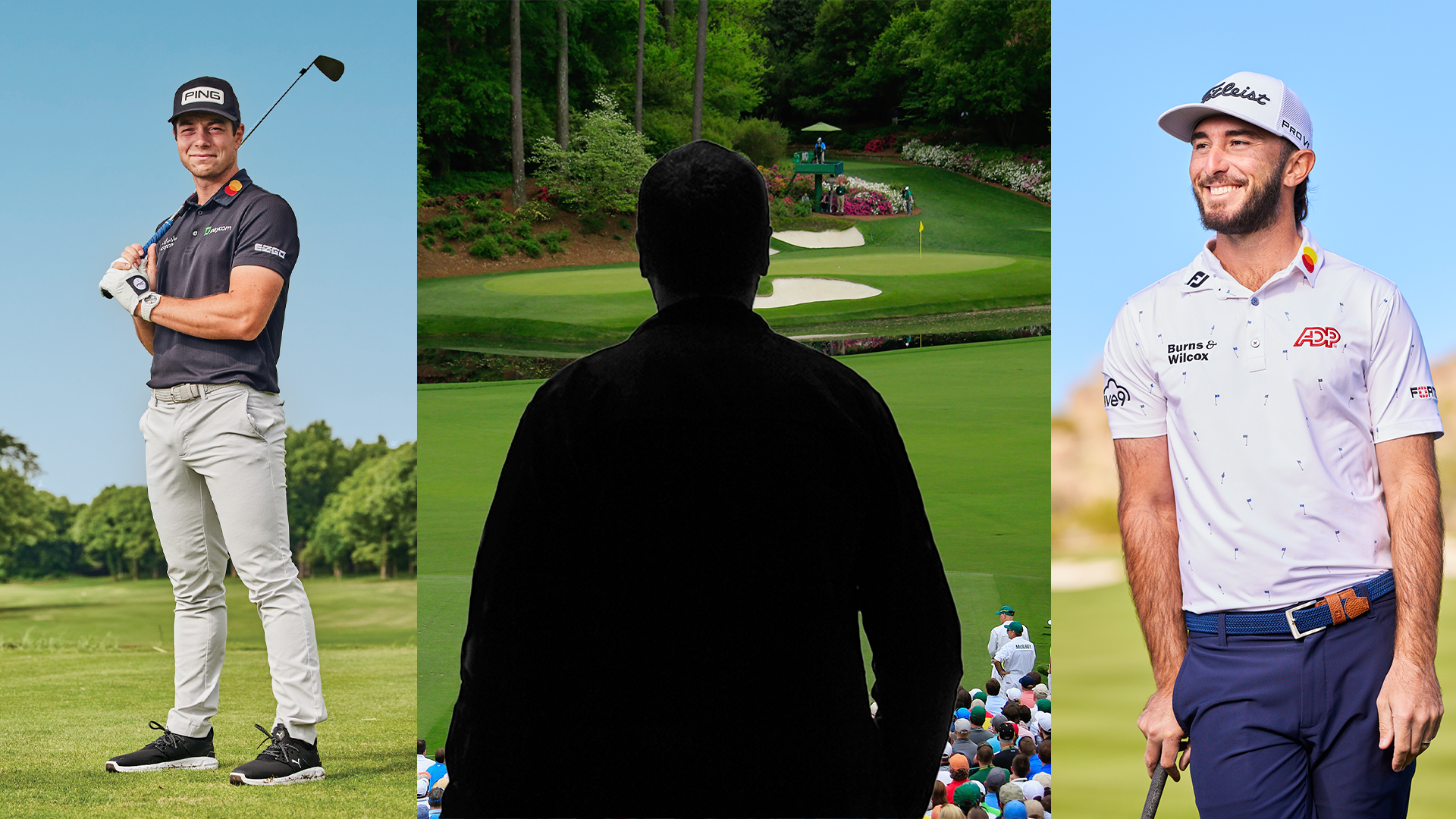

GOLF/Emma Devine

Jon Rahm slumps into a seat as he rips a crosscourt backhand.

It’s a Tuesday in late August at the U.S. Open — the other U.S. Open — but the world’s third-ranked golfer looks right at home.

Conversation with Rahm is a lot like tennis, a sport that he has followed since he was a child in Spain at the height of Nadal. Sentences fly back and forth at a whiplash-worthy pace, and Rahm’s words land with the intentionality of a well-placed forehand. Perhaps it’s an offshoot of learning English as a college student living alone in America, but Rahm possesses a tennis player’s economy of energy: he does not waste time looking for words — or saying them.

From a luxury box at Arthur Ashe Stadium, Rahm tells me the story of the first time he played tennis. The match was supposed to be a leisurely weekend outing with his wife Kelley at a court near their home in Scottsdale, but it quickly turned competitive. Rahm was annoyingly good for a first-timer, zipping volleys into open space with ease, but he was annoyed, too. He expected to be better.

Serving was particularly frustrating. He knew the technique, but he couldn’t get the ball over the net. He drilled a few serves into the mesh before Kelley, a former college javelin thrower and regular tennis weekender, taught him the proper form.

After a few minutes, Rahm figured it out. He smashed an overhand with all his might, watching it explode off his racket and paint the opposite corner for an ace. When his eyes met Kelley’s again, the roles had reversed.

“Okay, that’s enough,” Kelley said, visibly annoyed and heading for the exit. “We’re done here.”

Rahm laughs as he remembers the last thing she told him.

“Tennis is my sport. You’re not beating me at this, too.”

As we chat, our first few questions resemble something like a volley. He’s testing my range; feeling out my strengths. The first hint of this comes right as our interview begins. An early softball — do you like tennis? — is unabashedly blasted back into my face. (The response: “Absolutely.”)

Rahm’s message to me is clear: no more lollipops.

That’s good, because there’s ground for us to cover. His PGA Tour season ended just hours ago in a loss at the Tour Championship, the latest in a frustrating blip after he spent six months as the hottest golfer in the world. That might represent an understandable regression to the mean for most golfers, but not for Rahm.

I load up my first serious return of the interview — As we sit here today, how do you view the last 12 months of your life? — and for the first time all afternoon, I see his interest piqued.

“Oh man, I’m not sure how to answer that,” he says, his gaze softening slightly.

Fifteen-love.

THE ANSWER IS OBVIOUS: this has been the best year of Jon Rahm’s life.

Rahm has won a staggering six times since last September — a stretch that includes a Seve Ballesteros-tying third win at the Spanish Open; a dramatic win at Tiger Woods’ home event, the Genesis Invitational; and a DP World Tour Championship. The price of being that good at golf in 2023 is … high: Rahm’s $16.5 million earned in ’22-23 ranks second on the PGA Tour’s all-time single-season money list, and his list of endorsements — like Maestro Doebel, the official tequila of the other U.S. Open — has grown to a prodigious length.

But that doesn’t mean that Rahm thinks so. He is the rare kind of hyper-alpha competitor who seeks comparisons to the legends of the sport, basking under the weight of expectation that comes with them. He bristles when I ask why he mentions Tiger Woods’ name so often.

“I like to set goals for myself that I need to work towards,” he says. “It’s extra motivation to get up in the morning.”

His game has not always been Tiger-like during these last 12 months, oscillating from the Woodsian cyborg killer we watched steal the Genesis to the deeply frustrated mortal we saw after rounds 1 and 2 at the Open. As the golf world turns to the Ryder Cup, Rahm hasn’t claimed a victory in nearly six months, an eternity next to his self-imposed expectations.

While the dry spell is a point of frustration, there isn’t an ounce of worry about it taking a toll on his psyche. As he explains, his expectation is his superpower. He’s strongest between the ears.

“Golf is a game, if you’re on the golf course for five hours, action is what? Fifty seconds at most, every five to 10 minutes?” he says with a grin. “It’s a lot of dealing with your own thoughts.”

The most prescient reminder comes every time Rahm opens his closet to see a green jacket. That, of course, was the victory that made Rahm’s last 12 months: a four-shot throttling at the Masters that gave him his second — and golf’s most elusive — major.

He admits now that he woke on the morning following the biggest win of his life feeling terrible, mentally and physically exhausted from playing nearly two full rounds on a weather-delayed Masters Sunday.

He sat in bed the following morning staring at the green jacket in a state of groggy disbelief. It was real, but it didn’t feel real. Spare for the new attire, it was a Monday morning like any other.

Then Kelley handed him her phone.

“Somebody sent me a photoshop of Seve and I shaking hands wearing our green jackets,” Rahm remembers. “It was kinda funny, Kelley went from seeing me smile to seeing tears on my face.”

He pauses.

“I mean, I was absolutely bawling. In that moment, I realized what it meant.”

“THERE’S STILL A LOT TO DO,” Rahm says when the topic of legacy arises.

No kidding.

It’s been the best year of his life, but the line between very good and great is still blurry as it relates to him historically. He is about the only player in pro golf who can claim with some legitimacy that 21 career wins and two majors is only scratching the surface of his overall potential. If he realizes the entirety of that potential before he turns 40, he will be remembered as one of the greatest players ever.

It’s the hope of every professional golfer that the best is yet to come, and with Rahm, it might actually be true.

“I’ve done pretty well, but I’m still so early in my career,” he says in a tone not wistful but resolute. “Hopefully I can keep adding to it.”

Legacy means something different in professional golf today than it did when he arrived on scene — but Rahm’s disposition has not changed on the matter. He has proven a relentlessly independent thinker, irrespective of who that might offend.

In perhaps the most prescient example of that, he has retained a tight relationship with his longtime mentor and friend, Phil Mickelson, while maintaining his loyalty to the PGA Tour. That hasn’t always been an easy tightrope given Mickelson’s fraught relationship with the Tour, but Rahm has remained almost impervious to the awkwardness.

“Nothing about me has changed,” he says. “Just the questions I receive.”

What has changed is his perception of the ways he will eventually be remembered, particularly as he watches his hero, Tiger, enter the sunset of his playing career.

“You can do a lot of things for the game outside of competition to be able to build your legacy. Jack and Arnie did a fantastic job in that sense, and Tiger is trying to get to that point now,” he says, hinting at three legendary golfers turned golf course designers and investors, before offering a quick caveat.

“Right now, though, I’m still focusing on what’s happening on the course.”

And there’s plenty to focus on. Rahm arrived in Italy this week for the Ryder Cup with a fire in his stomach. Rome will be his third Cup start, but his Ryder Cup history has been strange. He struggled in his debut at Le Golf National in 2018 when the Europeans blew the doors off the Americans in Paris; then dominated at Whistling Straits in 2021 in an American romp.

“I want to win the Cup,” he says diplomatically at first, but he can’t avoid his own competitive instinct.

“I’m hoping this year will be the best of both.”

He loves the drama of match play, the excitement of trading shots, the history of the event. (In his press availability on Tuesday, he cited two Cups that predated his birth among his favorites, all-time. “I could probably think of more,” he said, only half-joking.)

In the quiet moments, though, his geekiness shines through for what it really means. It isn’t the tapestry that excites him — it’s the opportunity to add himself to it.

“When some of the all-time greatest of the game are telling you that they couldn’t even tee up the ball, their hands were shaking so bad going in there,” he says. “You’re like, ‘If you were like that, what the heck am I gonna be thinking in that moment?”

Rahm smiles as he says that last part. He knows exactly how the greats felt.

He’s hellbent on becoming one.