Inside a turbulent Masters: How Jon Rahm stole the show at Augusta

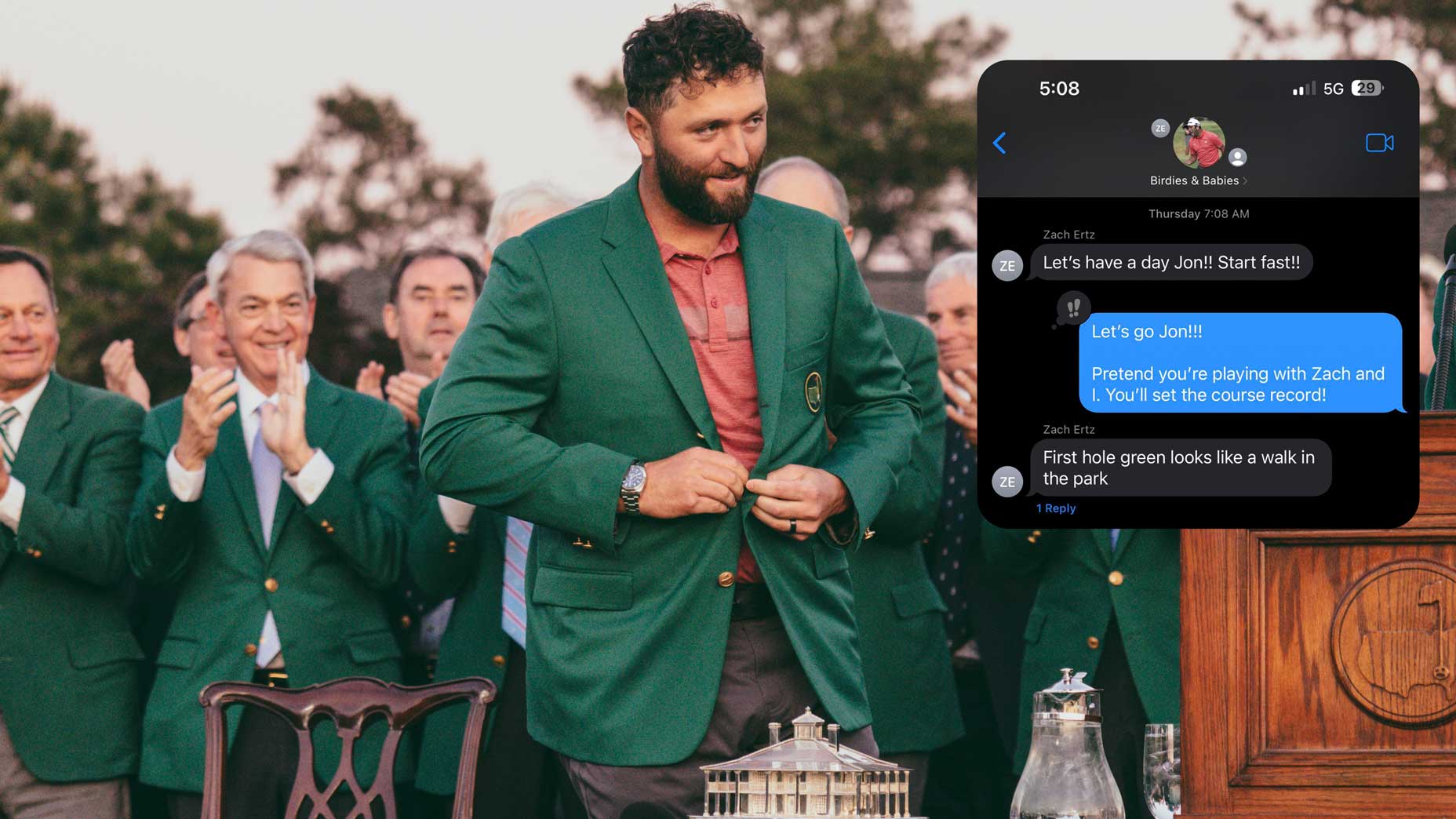

Jon Rahm is your 2023 Masters Champion.

getty images

AUGUSTA, Ga. — The moment Jon Rahm stepped onto Augusta National’s 12th tee on Sunday, his mind jumped to a childhood hero.

Tiger Woods had arrived at the same tee in the final group at the 2019 Masters. One group ahead, Brooks Koepka had just deposited his tee shot in the water short of the green, his chances sinking with it. Francesco Molinari and Tony Finau, Woods’ playing partners, soon followed suit, settling in the same watery grave that has claimed generations of Masters hopefuls. Two hours later, Woods was a Masters champion.

When Finau relayed that memory to Rahm during a practice round earlier this week, Rahm took note. But he had a follow-up question: Had Finau actually hit a good shot?

“Yeah, it was a good shot, it was just a yard too far right and spun into the water,” he told Rahm. The difference, he said, was that when Woods stepped up he aimed significantly further left, over the greenside bunker, content to find dry land and live to fight another day.

Rahm arrived at No. 12 with a two-stroke lead. He aimed left. He found dry land. After that?

“Hit a great lag putt, tapped it in and moved on.”

THE MOMENT RAHM’S THIRD SHOT landed on the 18th green, he felt a surge of emotion. And he thought of another childhood hero.

He’d imagined what this moment would feel like. He’d thought about this walk. He’d dreamt of winning the Masters ever since he knew it was something he could win. And now the four-shot lead he’d built guaranteed he was about to do exactly that. Fans continued to shout the same name they’d shouted all day in his direction.

“Do it for Seve!”

Sunday, April 9th, would have been Seve Ballesteros’ 66th birthday. It also marked the 40th anniversary of his second Masters victory. Rahm is a proud Spaniard. He’s a historian of the game. He knew the significance of the moment even as it was happening.

“I never thought I was going to cry by winning a golf tournament, but I got very close on that 18th hole,” he said post-round.

Behind Rahm, playing partner Brooks Koepka slowed his pace to a near-halt. He let his putter dangle from his hands, swinging back and forth, ceding the walk up Augusta’s green carpet to the soon-to-be champion, no doubt thinking of what could have been.

THIS YEAR’S MASTERS was always going to mean more. The invitees at Augusta National’s annual invitational tournament have always represented a variety of different tours, nationalities, ages and backgrounds. But they’d never quite collided like this. Even as the largest tournament of the year got underway, LIV’s power struggle with the PGA Tour hung in the air. Come Sunday, two competitors had separated themselves from the rest of the field. Rahm is arguably the best player on the PGA Tour. Koepka is arguably the best player on LIV. And now they were locked in head-to-head battle, a proxy showdown for golf’s larger war, the future of the pro game up for grabs.

There’s plenty to the divide. Money. Lawsuits. Insults. More. But that didn’t mean open hostility at the Masters. This is golf, after all — it’s not like Koepka and Rahm were likely to square up for hand-to-hand combat. The two get on well; they chatted for much of the third round and remained complimentary of each others’ games.

“I guess it is fractured, from the fan’s perspective,” Koepka said. “But as far as us, I mean, I think everybody saw it this week. It’s nice to see everybody.”

Koepka played a practice round with Rory McIlroy, the PGA Tour star who has most vocally defended his home circuit. Rahm played a practice round with Sergio Garcia, who’s a LIV golfer as well as the third Spaniard to win the Masters. After Rahm became the fourth, the first player to greet him was Jordan Spieth, an iconic PGA Tour member. The second to greet him was Phil Mickelson, the face of LIV. The rivalry is real. But the friendships are, too. It’s complicated.

FROM THE VERY FIRST TEE SHOT, Brooks Koepka never looked quite right.

In fact, he looked quite left. His 3-wood off the first tee went so far in that direction that Koepka barked at it to get lefter. His ball obliged by clearing the trees and settling in the ninth fairway, so bad it was good. He found the green from there and navigated a two-putt par — but the strangeness proved a sign of things to come.

At No. 2, his short birdie try caught half the hole and spun out. At No. 4, his tee shot sailed toward the pin but caught the top part of the front bunker, leading to bogey. At No. 6 his tee shot sailed toward the pin but kept sailing over the back of the green. Sunday at the Masters is known for its funnel pins, which reward precise shots with short birdie putts. But Augusta’s greens can funnel balls away, too. Koepka shrugged away the bogeys.

“Didn’t feel like I did too much wrong, but that’s how golf goes sometimes,” he said.

Koepka had started the day with a four-shot lead. He began the final round with a two-shot lead. By the time he bogeyed No. 4, he and Rahm were tied. And when he bogeyed No. 6, he lost the lead for good. He said later that he felt the same as he had the first few days. But he didn’t look it nor did he score like it. Even the pace of play, he said, had him thrown off.

“Yeah, the group in front of us was brutally slow. Jon went to the bathroom like seven times during the round, and we were still waiting.”

By the time Koepka bogeyed No. 14 and Rahm made birdie, he fell five shots back, crystalizing the final result. He soldiered on, logging birdies at 15 and 16, but there was plenty of walking and waiting and thinking to process the one that got away. By the time he reached his team — his parents, his wife Jena and his agent Blake Smith, who stood by scoring, cautiously awaiting his arrival — he seemed resigned to the result. The final round marked a small step backward after a massive leap forward. Last year he left Augusta with a missed cut and a bruised hand; he admitted trying and failing to punch through the window of his Mercedes courtesy car. This year he felt the heartbreak but felt the promise, too.

“I’d say probably give it a week and I’ll start to see some positives out of it and carry this over to the PGA, the U.S. Open and the Open,” he said. As to the question of whether he can win a major?

“Yeah,” he said, the answer obvious in his mind. “I think I proved it this week, no?”

RAHM’S GREATEST THREATS emerged from nowhere.

He and Koepka had built a beefy buffer between themselves and the rest of the field, but as the final round began that gap grew smaller. Their closest challengers from the second-to-last group, Viktor Hovland (who began the round at eight under) and Patrick Cantlay (six), slid into neutral, challengers emerged from further back.

There were past champs and big-time names among them. Defending champion Scottie Scheffler missed more putts than anyone but hit it so well he still made four birdies in his first 11 holes to get to six under, four shots back. Patrick Reed staged a furious eight-birdie rally and reached seven under. Jordan Spieth staged a furious nine-birdie rally, reaching eight under par with one hole to play, low enough to make Rahm take notice. But he bogeyed the last hole while his playing partner and chaotic golf predecessor, Phil Mickelson, made birdie to cap off an improbable final-round 65, posting the clubhouse lead at eight under par.

A word on Mickelson: Sure, he’s a three-time Masters champ and won a major just two years ago. But he’s also been out of form and out of sorts. He’s 52 years old. He missed this event last year, mired in LIV-related fallout. He entered with just one top-10 worldwide finish in two years, a T8 at LIV Chicago last September. Early in the week he was asked if he thought he had a chance to win and said, basically, that he thought it was unlikely.

“I’ve got to be realistic. I haven’t scored the way I want to,” he said. “But I do see a lot of positive signs.”

By Friday afternoon, however, Mickelson was ready to talk himself into something special.

“I’m going to go on a tear pretty soon,” he said, twinkle returning to his eye. “You wouldn’t think it. You look at the scores. But I’ve been playing exactly how I played yesterday, hitting the ball great, turning 65s, 66s into 71s. I’m ready to go on a tear.”

On Sunday, that tear began. There was very little to suggest that he would rally to a share of second place by week’s end. Very little besides that twinkle. But that was apparently enough.

Not every challenger was a past champion. There were others, too, Russell Henley and Cameron Young and Sahith Theegala, who stuck their noses into temporary contention. But none survived so well as the champion.

IT WAS A STRANGE WEEK at Augusta National. Forget the LIV drama and remember the weather. It was cold. It was wet. It was windy. It was muddy. It was ugly. On Friday, play concluded when several massive pines toppled over in the wind, miraculously missing every spectator in the area as they fled to safety in the nick of time. On Saturday, the second round finished in misery, with the final groups trudging up the 18th hole in 46 degrees and pouring rain. That afternoon, play concluded for the day when the greens began flooding past playable.

But at Augusta National, splendor is the status quo. And so the sun emerged on Sunday afternoon, as expected, and a proper Masters showdown began. Rahm was two shots behind. That was close enough.

“Well, it’s important to be in the final pairing, the closest pursuer,” he said before the finale. “My objective today is to focus on my own game and what I can control. Whatever Brooks does is whatever Brooks does.”

But as the day wore on, Rahm seemed to draw energy from Koepka’s chaos. He strode ahead in the fairways. He lobbed the pressure back onto his competition. He knew there was one man standing between him and his wildest golfing dreams, and he put the pressure on that man again, and again, and again.

“It wasn’t match play, but early on, it kind of felt like it, right?” he said. “So when I took the tee on 4, the goal is to keep giving him something to look at, meaning, if I hit a good shot, just for him to see that I have a birdie chance — keep putting the ball in the fairway and keep making good swings for him to feel more of the pressure rather than me, right? Let me be the one pushing.”

Rahm kept pushing. Koepka couldn’t hold his ground. And before long he wasn’t just the closest pursuer; his was the name on top of the leaderboard.

THE SINGLE MOST JOYFUL MOMENT of Rahm’s post-round press conference came when a reporter informed him he’d just become the first European man in history to win both the U.S. Open and the Masters. At first he couldn’t believe it. Once he started to believe it, he was overcome with emotion. The student of history was adding to it, too.

“Out of all the accomplishments and the many great players that have come before me, to be the first to do something like that, it’s a very humbling feeling,” he said. He followed with something rarely heard in press conferences.

“Thank you, by the way. Because I don’t know how I would have found out.”

The final question of Rahm’s day concerned his right leg. Rahm was born with a club foot; to hear him describe it, his foot was turned 90 degrees towards the inside, “basically upside down.”

The club foot explains Rahm’s move; if you’ve watched him play golf you’ve likely noticed his backswing is tremendously powerful but extremely abbreviated, too. The way Rahm handled the club foot explains something else about him, too: he’d never explained it to the media until the 2020 Open Championship, when somebody finally asked a follow-up question about it.

“I dropped hints as a professional in these pressers many times,” he said on Sunday. “Somebody finally asked a follow-up question, and I decided to talk about it. It wasn’t like a moment where I felt ready. It’s something I’m pretty open about. There’s a reason why I have the swing I have and the mechanics I have. It’s part of who I am.”

Rahm won the Masters because he’s embraced who he is. He won because where others might see obstacles, he sees opportunities. He won because he battled through bad weather and the bad end of the draw and the baddest major champion of the past decade. He didn’t win because he’s been the best golfer in the world for several years. But that made it more satisfying, for him and for us, knowing as Rahm joined his heroes as Masters champion, he deserved it, too.