Tiger Woods says he hurts ‘everywhere.’ An expert explains what’s happening

Tiger Woods' surgically repaired ankle is pain-free, but other parts of his body — including his leg, back and neck — are under increased strain.

Getty Images

The ankle bone is connected to the knee bone, which is connected to the thigh bone, and beyond.

Remember that nugget from Anatomy 101? We’ve got a good case study in Tiger Woods.

Woods himself has alluded to that fact on more than one occasion this week at Albany, in the Bahamas, site of his latest competitive return. Though his surgically repaired right ankle isn’t bugging him, he said, other body parts are “taking the brunt of the load so I’m a little sore in other areas.” Where, exactly? After Thursday’s opening round of the Hero World Challenge, Woods said that he was feeling it “everywhere.” He added, “My leg, my back, my neck. Just from playing, hitting shots and trying to hold off shots.”

No wonder.

“He’s borrowing from Peter to pay Paul,” Robert Forster says.

A Santa Monica-based physical therapist who has cared for 54 Olympic medalists and a Wimbledon champion, among other world-class athletes, Forster says that elite performers like Woods are different from the rest of us in their physical gifts. But they aren’t exempt from the laws of physiology. Because everything’s connected, issues in one area of the body, Forster says, can affect “everything up the kinetic chain.”

For Woods, the latest issue in a lengthy tale of medical woe involves the subtalar joint of his right foot, which required fusion surgery this past spring. The joint, which lies just below the ankle, between the talus bone and the heel, is not responsible for up and down movement. But “it’s critical,” Forster says, “for pronation and supination.” That is, the internal and external rotation that is central to the swing. After fusion surgery, Woods has lost that side-to-side movement.

“And if that’s not moving, if the foot is not rotating on the talus,” Forster says, “that movement has to come from somewhere else.”

One obvious source of compensation would be the right knee, Forster says, which would help brace the right side on the backswing while aiding in rotation on the downswing and follow through. “I would be looking for wear and tear on that joint for sure,” Forster says.

But when the ankle can’t rotate, other parts of the body are called into service, too. The hips endure more strain, and since the hips are connected to the back, which is linked to the shoulders, which support the neck. . . you get the point. The implications radiate from head to toe.

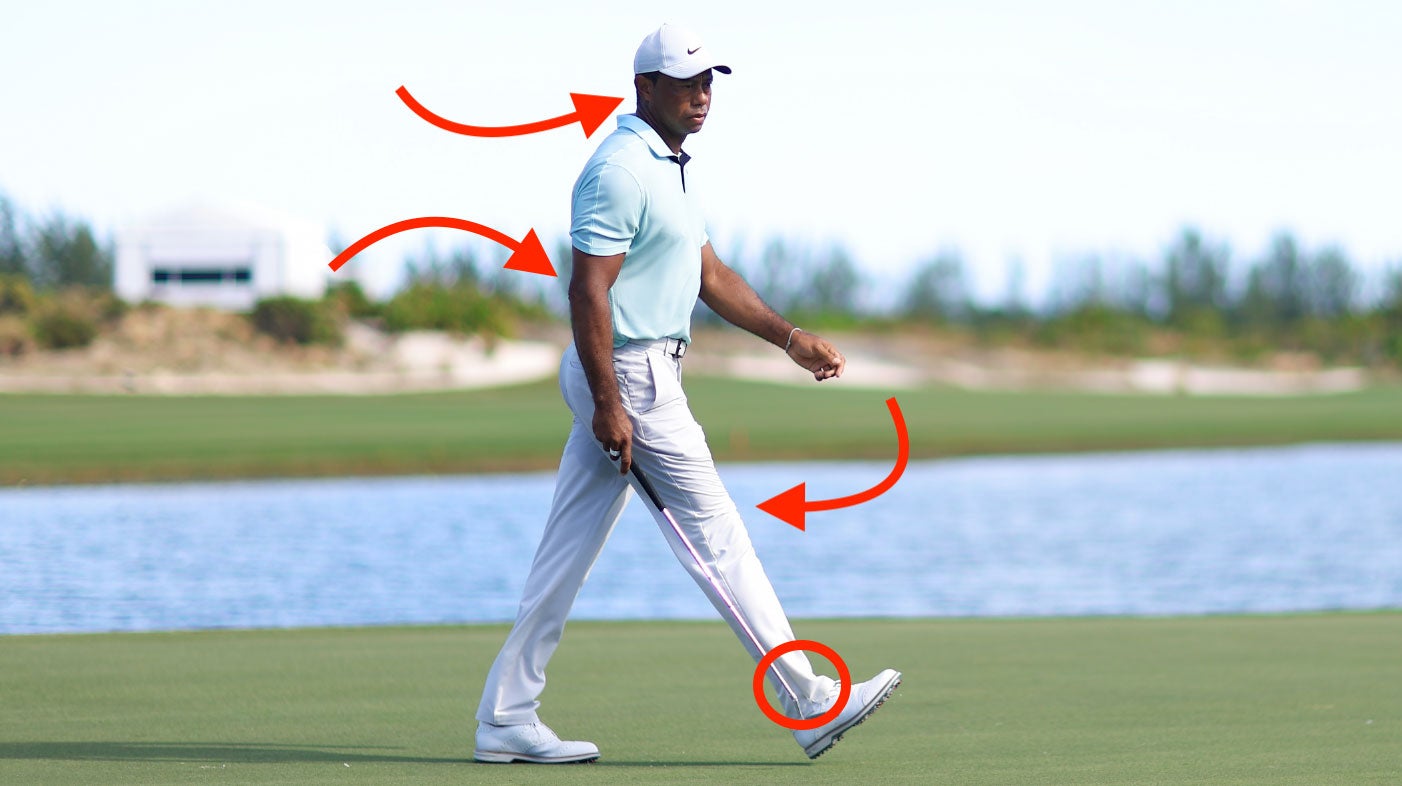

At the PNC Championship, the parent-and-child affair that Woods is slated to take part in later this month, Woods will likely use a cart, as he has in the past. But this week, he’s walking, and even that, Forster says, presents a different challenge now, as Woods is missing the “shock-absorbing function” that comes from pronation and supination of the arch, leaving other joints and muscles to take up the slack. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Woods has been seen moving with a slight hitch in his gait.

Even as he makes mechanical adjustments, Woods is adapting neurologically as well.

“The nerves in the ligaments around the ankle provide sensory information to the brain,” Forster says. “Subconsciously, the body is adjusting to different muscle contractions and firing patterns.”

Few golfers, of course, have been more adept than Woods at making such adjustments; this is a man who famously shortened his swing midway through the first round of the 1997 Masters, and went on to win the tournament by a record 12 strokes. Still, the neurological component is yet another challenge, and it squares with Woods’ assessment of his own swing, which he concedes has changed, though he says not all of those changes have been made consciously.

“That’s a big part of what makes him who he is,” Forster says. “It’s that remarkable proprioreceptive sense where he can just adjust in stride using his God-given talents.”

On Friday, in the Bahamas, feeling sore all over and wielding a subconsciously modified swing, Woods shot two under par, before slipping off to receive treatment. Rest. Ice. Elevation. Compression. All of those, Forster says, will be critical in his recovery. So will strength and flexibility training, especially in areas that are under increased strain, which, as Woods himself said, seem to be “everywhere.”

How long can one man’s body withstand that kind of stress? How much mileage does Woods have left as he embarks once more on the comeback trail?

Impossible to say, but the journey itself will be compelling theater.

“That’s the thing that excites me most, watching athletes overcome physical injury and geting back on their game,” Forster says. “I guess that’s why I am a PT, and they are superstars.”