It was the final week of Solomon Hughes’ life. The trailblazer who helped tear down barriers for Black golfers everywhere was dying of cancer at a hospital in the Minneapolis suburbs. He had a rare form of leukemia, and there was no cure.

In those last precious days, his oldest daughter Toni was granted permission to take her father off hospital property. Toni’s hopes were simple: she wanted her father to smell the fresh air, to escape the doctors and the machines, to have the small dignity of a few hours of his old life. She asked him if he had any final wishes.

“I want to go to Hiawatha Golf Course,” he said.

Hughes’ bed at the hospital overlooked Meadowbrook Golf Course, another Minneapolis muni. Solomon liked to gaze out the window at it, but Meadowbrook wasn’t his course. So the day they left the hospital, Toni bundled up her father and drove 11 miles east to South Minneapolis. It was time to take Dad home.

They stopped the car in the parking lot and scanned the front nine through the windshield. When he wasn’t playing or teaching here, Solomon loved to walk the course and study it. On Saturdays he’d have his son, Solomon Jr., caddie for him. Nearby was the spot where Solomon used to eat lunch, a sandwich from his wife, Bessie, back when he wasn’t allowed in the clubhouse. After years of eating outside Hiawatha’s cozy, Tudor-style home — including many a meal on the par-3 eighth hole, where he made two holes-in-one — Solomon was finally invited inside.

Today, though, there would be no clubhouse visits. Solomon savored the memories for quite some time from the passenger seat of his daughter’s car. Eventually, Toni thought it was time to leave.

“Oh no,” he stopped her, refusing to say goodbye. “Let’s drive around; I want to see the back nine.”

It was that day, Toni would later say at his funeral, when she realized how much the game truly meant to him. And how much he meant to the game. Eventually, others would agree, christening the clubhouse in Solomon’s name and inducting him into the state’s golf hall of fame.

Solomon wouldn’t live to see it. He died just days after that final drive.

Today, the Hiawatha legacy that Solomon Hughes helped create is at the center of the most complex topic in Minnesota golf. An issue of theft and ownership, historical preservation, ecological sustainability, a $43 million solution that satisfies only some and a future that threatens to wipe it all away.

This is the story of Solomon’s beloved Hiawatha Golf Course — a place where the definition of saving continues to be up for debate.

A HISTORY OF HIAWATHA

Hiawatha Golf Course sits four feet below Lake Hiawatha, a popular body of water and public park in the southeast corner of Minneapolis.

When the City of Minneapolis first thought to bring a golf course to the area in the early 20th century, it was an undeveloped square plot of wetlands. The city dredged some 1.2 million cubic yards of soil to form the lake, and the course — built on the dredged material atop the wetlands hard against the lake — was completed on July 30, 1934. Hiawatha Golf Course opened with greens fees topping out at 35 cents. The second nine opened a year later. Business was good, but the golf course soon faced problems caused by low topography, poor drainage, settling and climate change.

Over the years, walls were built to prevent erosion and pumps were installed to move stormwater over a berm and into Lake Hiawatha, which had already been ravaged by trash accumulation from storm sewers. In the 1990s the city doubled down on the golf course, adding new pumps, elevating fairways, tilting greens and adding water hazards as collection points to help with excess water.

Then, in June 2014, a record rainfall hit Minneapolis. The rain caused flooding across the state, but Hiawatha was hit especially hard, with four feet of standing water covering parts of the course. It closed for weeks. Hiawatha had flooded before, but the most recent rainfall had exposed the course’s inefficiencies and discovered that hundreds of millions of gallons of groundwater was pumped into Lake Hiawatha annually to keep the course playable (and protect basements west of the course from groundwater intrusion).

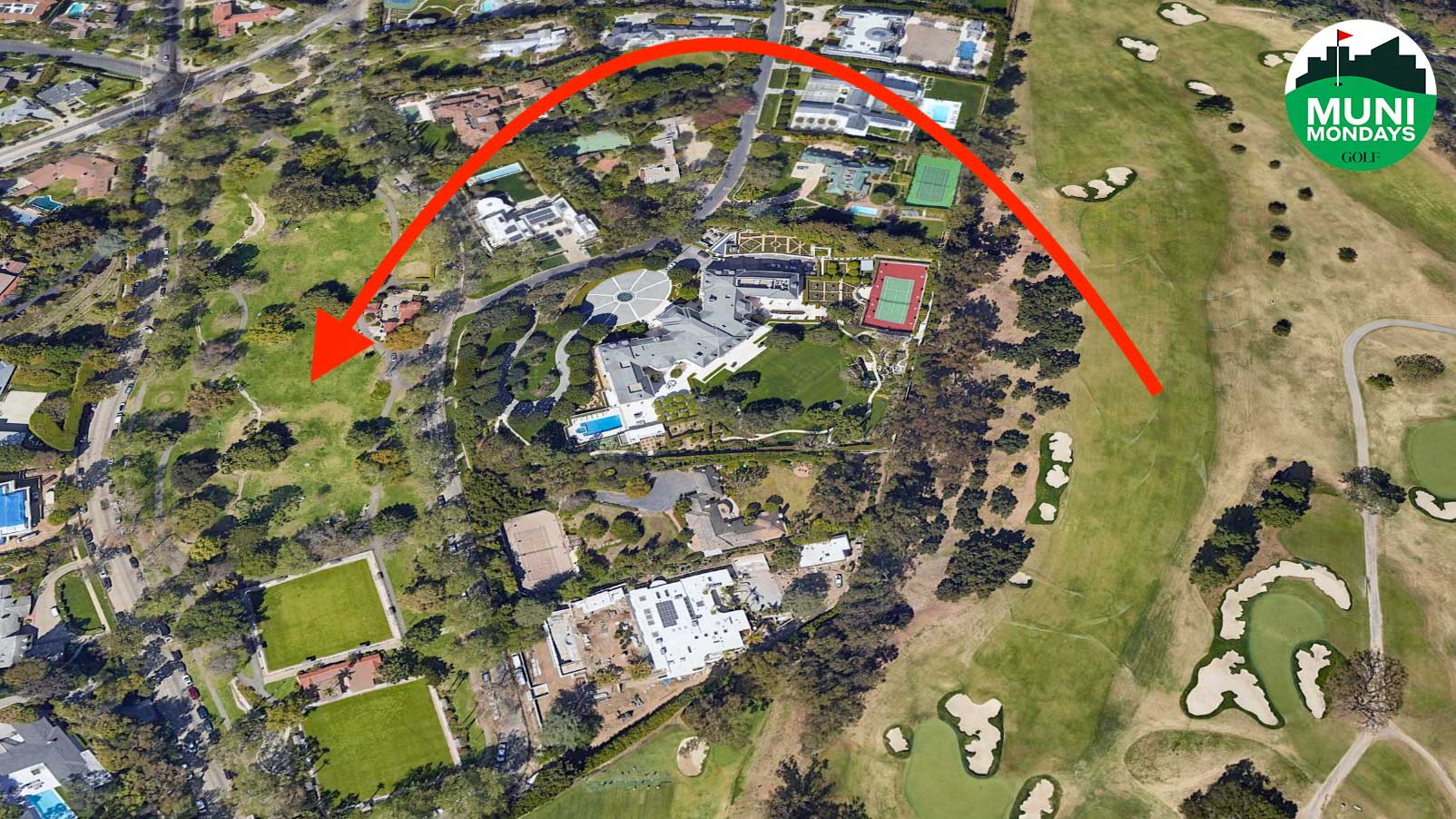

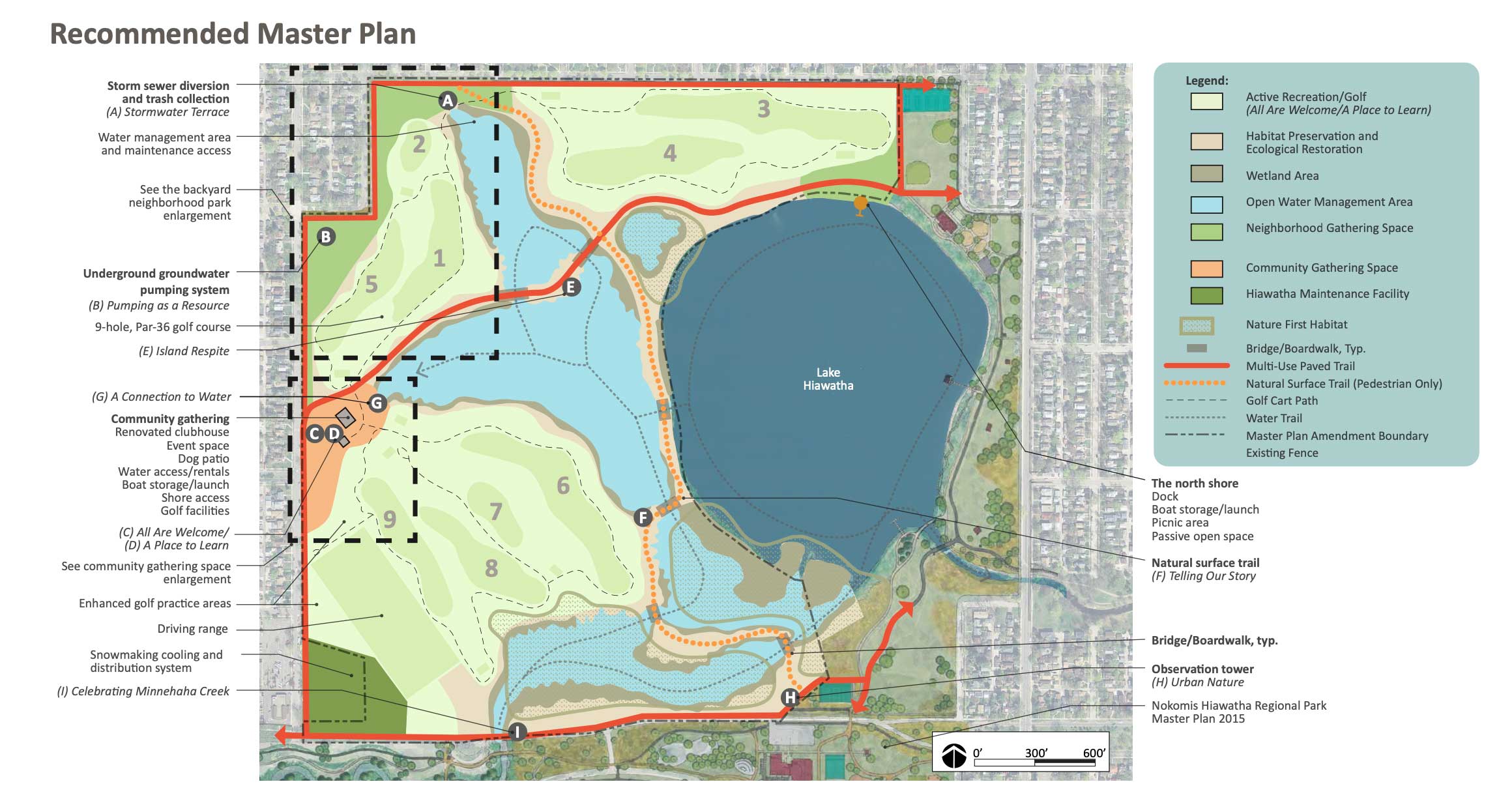

The Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board sprung into action, commissioning a master plan to re-envision the future of the park and golf course. That extensive plan — which provided much of the background for this piece — included new trails, picnic areas, beach access, a dog patio, ecological restoration and a revamped water management system to help with flooding. But it also required Hiawatha Golf Course to be reduced to nine holes.

The “compromise plan,” as it has come to be known in Minneapolis, divided the local community for nearly a decade, the topic routinely leading to well-attended and contentious board meetings.

Hardcore golfers demanded 18 holes with better drainage. Non-golfers wanted more access to a public space they could enjoy. Residents, many sick of trash accumulation on sidewalks, wanted the lake cleaned up. Others simply wanted more time, or a better plan from the city, or the parks board to come up with funding first. Some even preferred the status quo — offering that when the golf course floods again, they’ll just wait it out. The Dakota people, a Native American tribe that had the land stolen from them years ago, wanted the area returned to its original state. The nine-hole plan, in their view, was a compromise, and one most reluctantly supported.

When the board finally approved the $43 million master plan in September of last year, it was years in the making.

We stood in front of bulldozers before. We are going to stand up for Hiawatha Golf Course and the legacy of Sol Hughes and the other Black golfers.

“It’s kind of a nuanced deal, different from your typical course in the middle of a city; this is not that,” said Tom Ryan, the recently retired president of the Minnesota Golf Association. “It’s a unique situation. I haven’t heard of another one like it.”

But no group felt more betrayed than the area’s Black community. Three years ago, two miles from Hiawatha, George Floyd had been murdered on Minneapolis city streets. Now a city golf course with historical importance to the Black community — one of the first they were allowed to play and one still frequented by a significant chunk of the city’s Black golfers — was to be cut in half. As the debate raged on, Hiawatha’s trailblazers were brought up often. None more than the man for whom Hiawatha’s clubhouse is named: Solomon Hughes.

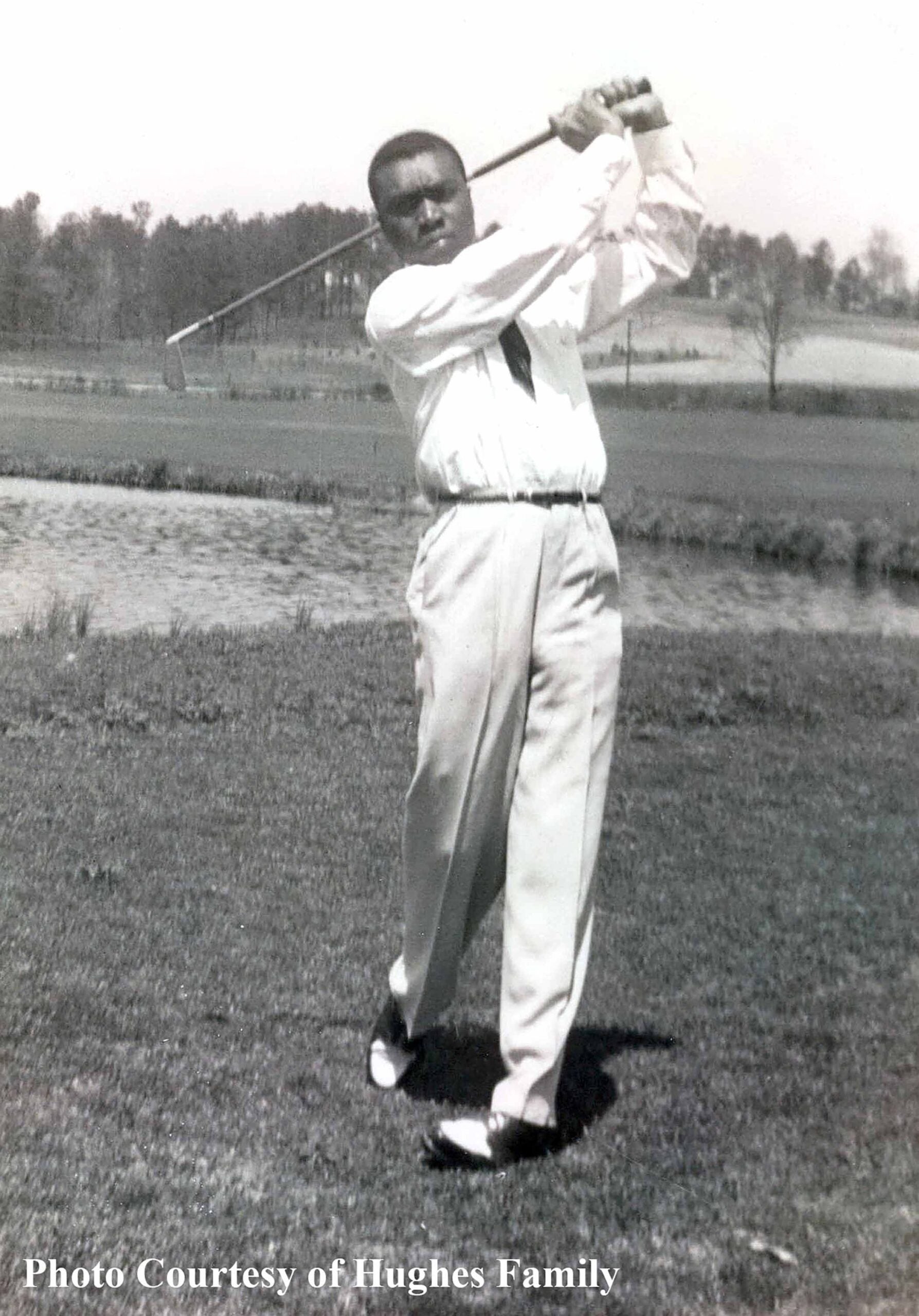

Hughes was born in Gadsden, Ala., in 1908, and from a young age he dreamt of becoming a golf pro, yet he and other Black players weren’t allowed to play on the Professional Golfers Association (now the PGA Tour). Instead, Solomon became a star on the United Golfers’ Association, golf’s version of the Negro Leagues, and won the tour’s National Negro Open in 1935 at age 26.

His celebrity spread, and soon he was rubbing elbows with boxing stars Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson, who were stationed at nearby Fort McClellan during World War II. Hughes, then a father of two (and eventually father of four), moved to Minneapolis in 1943 to escape the segregated South.

He picked up a day job working for the railroad but never strayed far from golf’s orbit. He continued to play golf in Minneapolis, supporting his second job by giving lessons and practicing at nearby Hiawatha Golf Course, which was just two miles down the road from his home.

Hiawatha was near a “redlined” area of the city — one of the few designated areas in Minneapolis where Black residents could live — and it was one of the first courses in the state to allow Black golfers on its fairways, though they weren’t yet allowed in the clubhouse.

For years, Hughes and other Black golfers lobbied for rule changes for non-whites, but it wasn’t until 1952 that the doors first opened. Seventy years later, in July 2022, the clubhouse was officially renamed in Hughes’ honor. There is now a Solomon Hughes Sr. Golf Academy.

“He was a professional golf champion who never bragged about his wins, never complained about his losses, and he was always willing to help people,” Solomon Jr., his only son, said of his dad at the naming ceremony last summer. Solomon Sr. often played in khakis, a dress shirt and tie with spotless golf shoes. He built his son his first set of golf clubs. “He carried himself with respect on and off the course. He was a pioneer of Black rights.”

Hughes kept trying to play on the PGA, especially when it visited nearby Keller Golf Course for the St. Paul Open. He and fellow UGA star Ted Rhodes were denied entry twice, but they broke through in 1952, several months after Joe Louis, competing as an amateur, became the first Black golfer to compete in a PGA-sanctioned event. Eight years later, in 1960, Charlie Sifford became the first Black golfer to earn his PGA Tour card, an effort due in no small part to Hughes’ efforts.

Hiawatha’s history in Minneapolis’ Black golf community extends well beyond Hughes’ accomplishments. As one of the first integrated golf courses in a golf-crazed state, Hiawatha served as a golfing home for famed Black players the world over. Even Tiger Woods stopped through; he once held a clinic on the 13th fairway at Hiawatha just weeks before he won his second major championship a few hours south at Medinah.

Tom Lehman, a Minnesota native and major champion who played at Hiawatha in his teens, is among the golfers who have gone to bat for Hiawatha’s preservation. He attended a board meeting last year in support of the golf course and even created an 18-hole routing that, coupled with engineering and drainage updates, he says could give golfers 18 holes and solve the water issues.

“Right now, there’s a tournament going on in Augusta, Ga., called the Masters, and Tiger Woods is playing,” said Lehman, speaking to park commissioners during a board meeting on April 6, 2022. “Tiger Woods is playing in big part because of what happened at Hiawatha Park Golf Course back in the 50s.

“Back then, Black men could not play on the PGA Tour,” Lehman said. “It’s a stain on society, absolutely, but you have people like Solomon Hughes, Jimmy Slemmons, Ted Rhodes, Charlie Sifford, who stood up and push and pushed and pushed. … Nine holes isn’t even close to what this course is all about — it’s based upon the history of Hiawatha.”

‘WE WILL BE STANDING IN FRONT OF BULLDOZERS’: A COMMUNITY CONTROVERSY

For years, the $43 million master plan to reimagine the space and eliminate nine golf holes was voted down by the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board. But as the commissioners changed, so did the votes.

“As a Black woman who’s seen history be erased, who has watched civil rights heroes’ legacy be torn apart, I can’t (vote in favor of the plan),” said LaTrisha Vetaw, a commissioner during a July 2021 meeting. “I can’t be the Black woman who sits on this dais and says, ‘Solomon Hughes and his children don’t matter, and all those hundreds of, maybe even thousands of Black people who have reached out to me about this [don’t matter].”

One particularly contentious, well-attended public meeting came on Aug. 17, 2022. That night was filled with passionate and fiery pleas defending all sides, including many non-golfers, who urged the commissioners to restore the environmental ecosystem and support the compromise plan. The public hearing portion alone lasted nearly two hours, with about 40 minutes dedicated to reading aloud some 50 written responses. (In the process of drafting the final master plan, four online surveys administered by the parks board brought in over 900 responses, and the final 45-day period to submit feedback generated more than 1,100 comments.)

“You guys don’t have money to do what we are talking about tonight,” Scott Persons, a Minneapolis resident, told the commissioners. “Please don’t approve this and move forward when we have a success story in our community that’s working. Three years ago I would have been here supporting the nine-hole compromise just like a lot of people up there, but hearing from the people using this [course], it’s vital to them. Please don’t move forward with this. We need more time.”

Sean Keir, a Minneapolis School District teacher and golf coach, explained the importance of an accessible 18-hole facility for the four Minneapolis high school teams and three other golf teams that practice there.

“Some of you have a grudge against golf, but this is a public course,” he said. “This is a course that’s open to everyone. This is a course that needs to be there for the youth that’s using it.”

Jonathan Carlson represented the Bronze Foundation, a group that wants to keep Hiawatha 18 holes and preserve its history. He asked the board to table the nine-hole plan. He called the movement critical, “for this George Floyd city.”

“The Bronze Foundation supports wholeheartedly the environmental aims of the flawed nine-hole plan to clean up Lake Hiawatha,” he said. “But the park board’s assertion that reducing stormwater impacts on Lake Hiawatha requires destroying the 18-hole course is false. The Bronze/Lehman concept shows that we can figure it out with necessary further community engagement.”

Finally it was time for commissioner Steffanie Musich, whose district oversees Hiawatha, to speak. Musich said she’d had many conversations with community members, scientists, climatologists and staff about possibilities over the past 8 1/2 years. She spoke slowly and carefully as she made her recommendation to advance the master plan to the full board for a vote.

“It is in a floodplain. It is going to flood again. It is a filled wetland that was filled with organic fill that continues to settle,” she said, taking a deep breath. “Understanding those things, and the fact that we can’t eliminate flood capacity, means we need to find a way to work with water in this location.”

Musich said the only path forward was to accept that Hiawatha would need to lose nine holes.

“We’ve spent a lot of time, energy and money trying to find a solution to the water problems here that would allow us to retain 18 holes of golf,” she said. “But with the restrictions in place around how you can change floodplain properties, there is not a way to do that that also allows us to plan for the future with our changing climate and achieve the environmental goals the community has told us over and over again they’d like us to achieve.”

But it was Bill English, a civil rights and social justice leader in Minneapolis, who provided the most powerful words of the night, offering one final plea for Hiawatha. He’d thrown out his prepared statements, he said, electing to speak from the heart.

“This fight is ridiculous!” he said, raising his voice. “If you can put a man on the moon, you can figure out how to protect the water and give us an 18-hole golf course which we deserve. We’re not going anywhere. We’re not going anywhere!

“I am 88 years old, but I look pretty good for 88, and I get around pretty good. This is gonna be a fight if you want to fight. We stood in front of bulldozers before. We are going to stand up for Hiawatha Golf Course and the legacy of Sol Hughes and the other Black golfers, people who contributed to the well-being of this city and state.”

Three weeks later, the board approved the master plan by a 6-3 vote. Hiawatha Golf Course would be reduced from 18 holes to nine, improving flood resiliency and returning some of the area to its restorative state.

Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey wouldn’t sign off on the plan out of respect for the Black community, but he chose not to use his legislative power to veto it. The $43 million master plan could go through, just without the support of the mayor’s office.

“We will be standing in front of bulldozers,” English said. “I can guarantee you that.”

A COMPLEX FUTURE

At 9:15 on a scorching July morning in Minneapolis, the fairways of Hiawatha Golf Course are already abuzz. A smattering of kids between the ages of 14 and 18 are out on the course, giggling their way through the thick, humid air; the younger ones tee off later. It’s not just any Thursday at Hiawatha: today marks the beginning of the annual Junior Bronze Tournament.

Solomon Hughes was a foundational figure in the Bronze Open Golf Tournament, now known as the Upper Midwest Bronze Amateur Memorial. The Bronze, which was first played in 1939, remains the longest-running Black-owned-and-operated golf tournament in the state, and has become a beacon for minority golfers in the upper Midwest. In the early years, the tournament was played at various courses throughout the city, but it has been played at Hiawatha full-time since 1968. The Junior Bronze, for youth golfers, has always been at Hiawatha.

But The Bronze won’t happen here if the course is reduced to nine holes. That’s no championship test, says Darwin Dean, the president of the Bronze Foundation.

Dean is in charge of tournament activities today, but right now he’s driving through the fairways in a golf cart, hot coffee in hand, administering yet another site tour. He’s done plenty of these over the years, and the highlights are always the same: the drainage areas; the man-made water-collection ponds; the lake, often closed due to high E. coli levels, that no one dare swim in.

It’s hot and muggy, but Dean is unbothered by the weather. He points to a nearby green, where a flagstick is gingerly flapping in the wind.

“Look at those flags blowing,” he says. “God blessed us with a breeze.”

These days, Dean has no choice but optimism. His Bronze Foundation is one of several organizations that have spent extensive time and effort fighting for Hiawatha’s future. The facts say that vision is imperiled after the advancement of the compromise plan, but Dean hasn’t given up yet on a Hail Mary.

“I stay positive because that’s the way life is supposed to be,” he says.

In the meantime, there’s much to be positive about. Dean raves about a boy who has blossomed in the Bronze Foundation Caddie Program — another offering for kids at Hiawatha, provided their GPA is 3.5 or higher — and speaks glowingly about the various charitable developments the foundation has advanced at the course in recent years.

Fueling some of Dean’s optimism is Hiawatha’s suddenly glimmering finances. From 2008 to 2019, Minneapolis courses combined to lose roughly $11 million, most of those losses — some $2.7 million — concentrated at Hiawatha. But golf boomed during the Covid-19 pandemic in the Twin Cities and elsewhere, resulting in record revenues at city courses in 2020, 2021 and 2022.

In 2021, Hiawatha recorded a rarity: a profit of $400,000. The good vibes continued in 2022, when the course made $1.47 million in revenue with a $133,061 profit — the second-highest total among the city’s courses. Of Minneapolis’ five 18-hole championship golf courses, Hiawatha has received the third-most play over the last four years (roughly 41,000 rounds per year).

Like most munis, operating budgets are tight. During the 2014 flood, Hiawatha was one of two city golf courses that suffered severe damage, resulting in $969,000 in FEMA grants for repairs and improvements. According to the Minneapolis Parks and Rec, $173,000 of that federal money went to Hiawatha for two new mowers and miscellaneous driving range equipment. The rest of the funds were distributed among the other city courses.

Dean wishes more of that money would have been spent at Hiawatha. He alleges the parks and recreation board hasn’t done enough to help the course, thus making it easier for the public to get behind a complete overhaul.

“I’ve seen much older lawnmowers out here than that one right there,” Dean said while a mower rumbled by during our site tour. “The park board purposefully starved this golf course out, trying to make it one of the worst golf courses around.”

Hiawatha won’t soon be on any Top 100 Courses lists, and it’s not hard to find golf in the Minneapolis area with greener grass and more pristine bunkering, but the truth is Hiawatha remains irrepressibly charming, even with some spotty greens and burnt-out patches. The proximity to the lake makes for gorgeous scenery. The Minneapolis skyline sparkles in the distance.

Irrespective of funding, Dean says, there is no draining Hiawatha of its history. He slowed down as our cart approached the 13th hole, the place where Tiger Woods and his father, Earl, put on a clinic in 1999. Woods was just 23 at the time, two weeks away from winning his second major. He gave tips to a select group while about 1,000 other parents and kids watched via a makeshift amphitheater off the fairway.

The 13th won’t exist anymore under the city’s current nine-hole master plan. The fairway that Woods once strolled will be split in half; part open water management area, part habitat preservation and ecological restoration zone.

In an effort to salvage 18 holes at Hiawatha, Dean and his foundation created what they call the “Alternative 6” plan. Dean hired a former water engineer from the parks and rec board to draft the plan, which focuses on water resolution built around 18 holes of golf. That plan was introduced to the city on April 6, 2022, but was panned for failing to fix a few key environmental issues.

Dean maintains the Alternative 6 plan is the best option for Hiawatha’s future — a point he reiterates as our site tour comes to an end. He hopes the city will reconsider it paired with Lehman’s routing. This past April, Hiawatha was added to the National Register of Historic Places for its association with the Black golf community. Maybe that will buy some time for his side, he says.

Nothing will happen soon. The master plan lays out an eight-plus-year timeline for the “new” Hiawatha Golf Course, with groundbreaking tentatively scheduled for 2027 and a grand opening for 2029. The parks and rec department now must raise tens of millions of dollars through donations, grants and other sources to fund the development.

One potential source of funding, the Hiawatha golf community, isn’t likely to be much help.

“It’s more than just 18 holes,” says Eustace Kesseh, a 37-year-old course regular and father who routinely plays Hiawatha on Sundays with his young family. “There are so many events that happened here to really bring the community together — The Bronze Tournament, celebrating Solomon Hughes, those are the things that bring people together to share experiences, the things that are more than just golf. There’s a heritage to it.”

Heritage has long been hard-earned at Hiawatha, which explains why those closest to the course seem so unwilling to part with it. As Dean drops me off at my car at the far end of the parking lot, he finds another sign of history hiding in plain sight.

He points to a spot at the far end of the asphalt, a good 50 yards from the clubhouse. It was near here, not long ago, that Toni and Solomon Hughes Sr. spent some of the final hours of his life. It’s no wonder Solomon chose this spot. Dean says the Old Negro Golf League, a group of about 40 or 50, uses the area to turn in scorecards and mingle after their regular Tuesday game. Sometimes they pray.

“We call it Amen Corner,” he says.

The men of Amen Corner still love Hiawatha. They aren’t alone.

As if to illustrate his point, Dean points again.

“This would all be gone,” he says. He steps on the gas and speeds away.

****

PHOTO CREDIT, TOP OF PAGE (FROM LEFT): Josh Berhow (inset)/Jeff Wheeler, Star Tribune via Getty Images/Josh Berhow/Courtesy of Hughes family (inset). Graphic: Emma Devine.